Where is Your God?

On necessary companionship

Near the shaw, a tired woman leans by the tree shed. Her skin carries more than a thousand lines holding on like a withered book. Under the shade, she clutches her beads tightly, repeating a chant so deep, a song as smooth as silk.

She's laughing. She's crying. She's confiding.

She's climbing the rope.

To become a mummy, Buddhist monks practicing Sokushinbutsu must undergo a fat-free diet and then be sealed in a ventilated tomb underground. They must ring a bell every day until they pass away from thirst. Then, their mummified corpse is kept for a hundred days before extraction. The more intact the body is, the better the ascension.

While this act of self-suicide was banned in the 19th century, it has always fascinated me. The ultimate devotion from the pious to override our primal fear of death is admirable. Even more, to remain sane in a dark, mute, isolated tomb for days on end is flatly impossible.

In the Kurikara Buddhist Temple in Tsubata, I had the opportunity to try out a similar experience. Nearly three meters underground, one must walk in total darkness and silence. The air was frozen. I could feel my heartbeat. All my senses were useless. When I emerged, it felt as if I were in hibernation.

I’ve always been envious of true worshippers. The way they sit in prayer or meditation. The conversation with their higher force of choice. They laugh and cry with their god. They appreciate their existence (correct, no matter who you attribute “their” to). They seek guidance from the higher powers. They smile when they are blessed. They cry when they’re tested.

The average person does not possess this devotion, this dedication, this figure…

I wish I had that support.

Where’s Your Lifeline?

There is a loneliness epidemic.

It is not gender nor race-specific. It is a divide created by the algorithm and late-stage capitalism. You’ve felt it. I’ve felt it. We all want a community. No, more deeply, we want someone who understands us.

We want a person who we can text about that cute cat on the way to work. Someone to complain about how shitty that one customer was. A plus-one down to go for a midnight walk to clear the head. An ear to yap to, a shoulder to cry on, and a warmth to feel.

This specific desire, I find, is similar to the relationship between a worshipper and their god. In the absence of a person, it is sought through a higher power. It is so strong that it makes life worth going through it is the answer to existence.

The Bali matcha influencers would call it spiritual healing. The bearded radicalists call it faith. The romantics probably would say it’s love…they’d be right. The person we love represents all of the things mentioned above and more.

We love the love our significant other (sorry polygamists) gives us. The inter-connectedness, the motivation, the attention… it all falls under what that inherent desire entails. But it would be unfair to claim that only a partner can do this.

I ask you: does this love, this emotion, not extend to a non-partner? How complete we feel, with someone by our side, is the same feeling a worshipper feels praying to their god. That someone can either be your best friend or your ‘totally working out’ situationship.

And I ask you again: Is this desire fulfilled only by relationships? A child seeks this feeling from their parents. An elderly person finds it through their legacy.

From the moment our umbilical cord is cut, we grasp for a lifeline.

This essay is an exploration of who throws us a lifeline during our lives. From when we first open our mouths to when we close them for the last time, who fulfills our inherent desire for love? For rapport?

Where is our god?

Goo Goo Ga Ga:

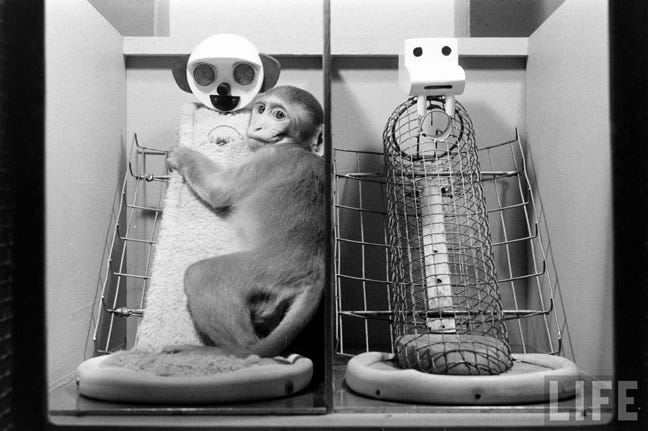

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow, an American psychologist, conducted a controversial study comparing a cloth mother to a wire mother to test the nature of attachment in infants.

Essentially, he made two mothers. One was made entirely out of wire mesh: cold, barren, and devoid of character, but it held a bottle of milk. Another was made of cloth: warm, welcoming, and full of humanity, but it offered nothing else.

The infant monkeys, for the most part, chose to cling to the cloth mother. They only returned to the wire mother when they were hungry. The test proved, to an extent, that infants (including humans) attach to their caregivers for reasons more than sustenance.

The unethical experiment shows that, from our earliest moments, we are born with the inherent desire to seek love. Most times, this role is fulfilled by our parents. We worship and idolize them in order to reap the blessings of food, safety, and tenderness.

It is poetic, in fact, that in our youngest of states, we know nothing but to love and seek another.

The First Quarter

I want you to think back when you were around 14-15 years old. What did that look like? Most likely, there was a friend or two with whom you hung out every day. You probably texted them after the school day was done, too.

Assuming you were not homeschooled or bullied, there was always someone in your circle with whom you interacted constantly. It could have been your best friend, sibling, or high school sweetheart.

What matters is that they were constantly present for you. They helped you during your hardest times. They were a lifeline.

Truly, that’s the symbol that I want to showcase in this essay. The first quarter of your life (I know it’s not mathematically a quarter, but symbolically) is ripe with lifelines. The system’s structure encourages you to do so in the first place.

You have a shared environment to meet people, there’s a determined frequency on how often you interact with them, and there is a shared experience to help you connect with others.

How can you not acquire a lifeline rope or two?

These people become essential to your upbringing and well-being. They are an outlet and an inlet at the same time. There are ample opportunities to create strong memories with them.

During this time, rarely do you need a lover to satisfy these social and love needs. A friend or two suffices. In short, for the first quarter of your life, your need for love, your lifeline, can easily be found through your everyday friends.

So-called “Adult”

As you grow and graduate, friends start moving, your schedule gets busy, and your attention becomes limited. There are fewer and fewer chances to meet, and in case it does, it is harder to connect. We become hyper aware of ourselves, of what differentiates us, and of the other.

Interestingly, we see a reversal in the lifeline supply. When our resources are sparse during this period of our lives, we can only afford to nurture a select few. In most cases, this is our partner (once again, sorry polyamory).

Our lover becomes the person who we get to see on a frequent basis (could be daily), who we vent to, who we want to share our experiences with, and who is there for us. Meanwhile, friendship takes a backseat and becomes a periodic event where we are stuck eternally playing the game of catch-up with another.

Tragically or ceremoniously (it depends on the person), the roles are reversed. The lifeline remains, the supplier differs.

No matter how much our hair greys or our bones creak, we are fated to remain the infant monkey balancing between the cloth mother and the wire mother.

Some relationships we invest in because they make us feel good. Others, like a coworker, boss, or parents, are nurtured for our survival. They are not mutually exclusive, of course, but the paradigm remains nonetheless.

Stuck-in-Nostalgia Millennial and Bitter Boomer

As much as I want to expand on this essay/article, I’m not nearly crazy about F.R.I.E.N.D.S. nor care about Eminem, to know more about the lifeline situation post-young adult.

If I were to say something, I suppose that the status remains the same even after reaching an older age. We get married, we settle down with family, we fortify the rope into a steady anchor.

But maybe, just maybe, as I see elder tourist groups having a laugh in an old-style Japanese cafe, as I see two blokes having a pint, I am filled with hope that there is a balance.

When we have more time, more autonomy, more resources, we can strike a balance between relying on our partner vs our comrades for lifelines.

And in an almost-cliche wholesome chungus conclusion, we mustn’t forget that we are lifelines for others too. We have influence over others. We have the freedom to choose who to provide a lifeline to.

We are our own gods.

Special thanks to the fierce Spanish PhD goldlocks girlboss for making the idea of this article happen. If you are reading this, you know who you are.